Ed Bremson

APW Poet Blog

March, 2012 (Archived)

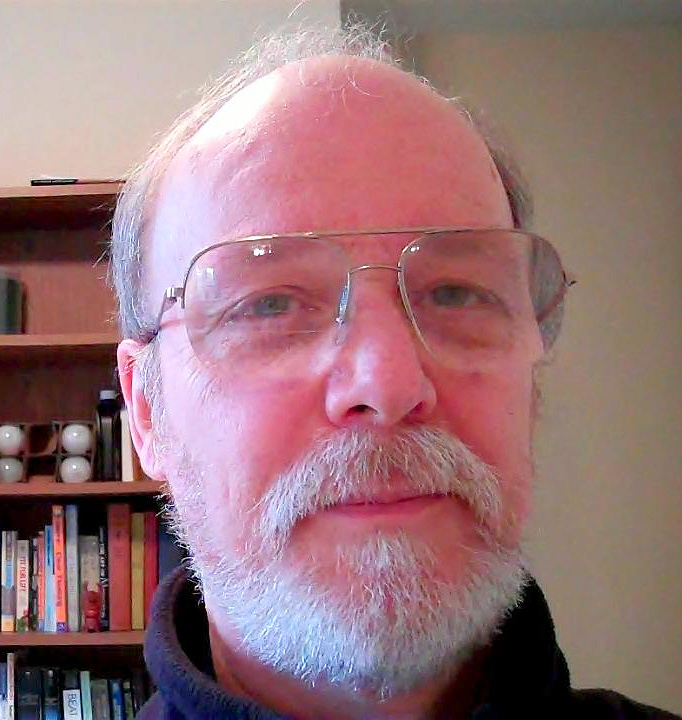

Ed Bremson

Ed Bremson was born in Raleigh, North Carolina and has lived there all his life. Ed earned his undergraduate degree in Philosophy from North Carolina State University, and worked in the Reference Department of the campus library there for ten years before leaving to become a stay-at-home dad. Currently he is a retired State employee. In 2009 Ed earned an MFA in Creative Writing, with an emphasis in Poetry, online from National University of California. Since that time he has published more than a dozen ebooks online. He also edited and published two ebooks of haiku – The Longan Tree, and My Old Blue Sky – by young Vietnamese poet Vy Vo.

Ed has been a member of The Longview Writers in Raleigh, 1968 – the present. Notable local writers from that group have included Peggy Hoffmann, Suzanne Newton, and Campbell Reeves. He was also a member of Bruce Lader’s poetry group for several years in the 1990s. For many years Ed was a struggling – and unsuccessful – novelist. Still, however, he managed to publish a dozen poems in small journals during all that time. Recently his poem “Pascal’s Advice” was published in the Longlist Anthology of the 2011 Montreal Prize contest; two of his poems were published in Frogcroon.com; two more published in Tuckmagazine.com; two of his haiku were published recently in the Japanese journal Asahi Shimbun; and he has a poem forthcoming in the Wisconsin Review.

Ed is an active contributor of poetry on Twitter (@EdBremson) and Facebook. He also is a regular publisher of haiga via his blog.

Email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 3, 2012

Advice From an Old Man

My name is Ed Bremson. I am your guest blogger for March.

I am mainly a haiku poet. Somehow it just worked out that way. When I discovered haiku, I discovered that I loved it. Writing haiku has given me much joy, and it’s hard to argue with results like that.

I think it is important for any writer to discover, as quickly as possible, what he or she likes to do, and then do it. When I was young, I was a pretty good poet in some respects, but I wanted to be like Hemingway and write novels. It turns out, however, that I was not a very good writer of fiction, so I basically wasted 40 years trying unsuccessfully to write novels. Finally I returned to poetry and have been pretty happy ever since. So, it is important to find out what you like to do, what you’re good at doing, and above all it is important to be honest with yourself.

The emphasis should not be so much on what you want to do as what you enjoy. Whatever you like is what you will do well. When I was young, people would praise my poems, but I would disqualify it and say, “Yeah, they like that, but I really want to write a novel.” In my opinion, that was really stupid on my part.

Anyway, if I occasionally (or even constantly) return to haiku, it is because haiku has been good to me, and I’m just returning to my roots, so to speak, because every good thing derives from that. Having said that, I also plan to discuss Kay Ryan, Wislawa Szymborska, Dorianne Laux, et al.

Follow me at Twitter (@EdBremson) if you want to, or Facebook. Let’s have fun this month.

My email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 4, 2012

Is everyone familiar with The Montreal Prize? In 2011 they instituted a new contest where they called for entries from around the world and gave the winning poet $50,000 for one poem. I wrote and entered two poems. I think the entry fee was like $20 each, but a smaller fee for third world poets. There were more than 3000 entries. Out of those, they cut the field to 150. I was certainly happy when I made that first cut. I didn’t make the second cut, however, down to 50, but they did publish all 150 poems in an ebook known as The Longlist Anthology, so that was really cool. You can view the ebook here:

http://montrealprize.com/anthologies/longlist-anthology/

You can click on the book image that says 2011 Longlist, and there is also another link. Below I have posted my entry in the 2011 Montreal Prize, Pascal’s Advice:

Pascal’s Advice

All the misfortunes of Man come from his inability

to sit quietly in his room alone. – Blaise Pascal

I am an old man, and I am content to sit

alone in my room. As a young man I never

really believed I could feel this way, but I guess

I had to live this long in order to reach this point.

Oh, I spent time out in the world long ago,

and like Dostoyevsky’s Underground Man,

when I came back home I would beat the walls.

I had so little then and desired so much. Now I

desire nothing, consequently I am rich. And I can

sit here alone, no longer having to make

other people happy, only myself. Besides, they’re

all gone – two wives, my parents, all my friends –

and there’s no one else to please. Alone in my room

the walls are my friends, the walls keep me safe, and I

no longer beat them. It has taken me a long time to arrive

at this place, but I’m glad that I’m finally able

to take Pascal’s advice. Of course you can’t close out

all the problems of the world. Pascal was wrong about that.

But if you can be content to sit in your room, you can

be happy, and keep the sadness out, and that is everything.

Email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 5, 2012

Every serious poet these days needs to have read at least some of The Triggering Town by Richard Hugo. I am so glad I had to read it for my Master’s degree. If you haven’t read it already, here is a link to a website that contains the first two, and possibly the most important chapters.

http://ualr.edu/rmburns/RB/hugo1.html

Much modern poetry today is based on the principles laid out in this book. One problem for me: I wonder how many people reading poetry today are familiar with the theories of Richard Hugo? And taking that a little farther, how many publishers publishing poetry are familiar with The Triggering Town?

The reason I mention this is that, sometimes I try to write poems based on those theories, and they are rejected. I just wonder if the publisher understands what I am trying to do in the poem. One other thing, however: many publishers today are driven by considerations of trying to sell your book to the public, and much of the public does not want to read experimental poetry. I can’t say I blame them. At the present time I would much rather read Billy Collins than Frederick Seidel.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 6, 2012

I have had a request to say a little more about Richard Hugo. The following is taken from my Master’s thesis:

One problem I used to have when writing poetry was deciding how to end my poems. I grew up, I suppose, in a very conventional poetic tradition. For a long time I believed that all the words, lines, and stanzas of my poems should follow each other logically until I had a finished poem. The only problem with this approach was that it was not always possible to adequately develop a poem logically – sometimes I ran out of things to say – and consequently I ended up with a lot of unfinished poems. Certainly there were poems which sprang rather fully formed from my brain, and those were really precious, but there were many other poems that required more work to make them complete. In the advanced poetry classes of my Creative Writing program I gradually learned that if I found myself not being able make logical associations in my poems, then I might want to try making imaginative associations, and that those could be just as valid, if not more so. Finally, when I read the first couple of chapters of The Triggering Town, by Richard Hugo, I was able to put away some of my preconceived ideas about poetry and open myself up to a more contemporary view. Hugo taught me that I did not always have to follow one subject to its logical conclusion. In fact, more often than not contemporary poetry does not follow one subject to its logical conclusion. It probably follows it to its imaginative conclusion. Hugo tells his readers “Make the subject of the next sentence different from the subject of the sentence you just put down.” (4-5) Of course this is a rather extreme dictum, to which I personally would not want to adhere. But if you only follow this advice occasionally you will create some truly remarkable poems.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 7, 2012

Since we’re talking about Richard Hugo I would like to say that when I was studying poetry, there was some discussion of the notion of “Leaps.” A Leap is like when you start out talking about one thing, and at some point you leap and start talking about something else. Richard Hugo seems to be talking about Leaps in The Triggering Town. As I recall, we discussed Leaps in relation the book Elegy by Larry Levis (a poet whose work I have not been fond of, although his poetry is important, I think.)

Be that as it may, here are some discussions of Leaps:

http://www.writersdigest.com/writing-articles/by-writing-genre/poetry/poetry-the-leap

According to the article, apparently Spanish poetry is known for its use of Leaps – Garcia Lorca, Neruda, et al. That was a surprise to me. I took a class on Garcia Lorca and we did not discuss Leaps at all. And more surprises: Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and Robert Lowell have at least dabbled in Leaps.

http://www.english.illinois.edu/maps/poets/a_f/bly/bushell.html

This is a good article on Robert Bly, who was also mentioned in the previous article

If you Google the words poetry leaps or poetic leaps you get articles like the ones above. That way you can explore this concept further, and might even want to incorporate some of these principles into your own poetry.

I think this is enough about all that for awhile. Tomorrow I plan to go on to something different. Thank you.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 8, 2012

When I was forty, I discovered Brenda Ueland. I wish I had discovered her when I was twenty. Her book If You Want to Write is really wonderful. It talks a lot about the imagination and how to use it. Kaye Gibbons once said that the hardest thing she had to do as a writer was learning to work with her imagination, and I daresay that is true of many writers. Of course Ms Gibbons was speaking of writing fiction, and if I recall correctly Ms Ueland also spoke mainly of fiction, but poets need to use their imaginations also, and they need to learn how to use it.

There are a lot of books out there these days that discuss right brain techniques in creativity. I enjoyed learning about clustering from Gabriele Lusser Rico in Writing the Natural Way. And Becoming a Writer by Dorothea Brande, although rather old, is very helpful with regard to the imagination. In the final analysis, though, perhaps the best attributes a poet can have are: the ability to daydream, and the ability to get some of those musings down on paper.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 9, 2012

Last year I read most if not all of Dorianne Laux’s poetry. She teaches at the University here in Raleigh, and the campus library has all of her books, so I checked them out one at a time and read them. Some of her poems are really good. I particularly liked poems like “Fear” from Smoke:

http://www.eons.com/groups/topic/1509430-Fear-by-Dorianne-Laux

and “What’s Broken” from Facts About the Moon: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/238770

Early in her career Ms. Laux used a lot of crude language, subjects and words that I would never personally use, mainly about sex. Now, later in her career, she has become famous. Garrison Keillor even reads her poems on the Writer’s Almanac, and The Book of Men, her most recent collection, seems to be aimed at a more mainstream audience.

Anyway, while I was reading the work of Ms. Laux, I wondered if her poem “Trying to Raise the Dead” http://goo.gl/IAeM1 might have served as inspiration for Mark Halliday’s “The Case Against Mist.” http://goo.gl/Byn3d In her poem Laux says, “What are you now? Air? Mist? Dust? Light?” and Halliday’s poem is “A Case Against” his being mist. Of course I can’t prove the two poems are related, and it probably doesn’t matter, but it’s an interesting piece of detective work to try and make that connection.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 10, 2012

How to Write Haiku

As I said at the beginning of the month, I am mainly a haiku poet. I have written thousands of haiku. I have studied them and written about them. At this time I would like to talk about them in more depth. I think both the reader and I will benefit from this discussion.

There is one good thing about the haiku: it is structurally so simple that, for the most part, one might discover how to write one by looking at a number of master examples and analyzing how they were written. That is what I propose to try and do here. I think we will find that aside from the seventeen syllable rule, the three line rule, the 5-7-5 pattern rule, and season words (in Japanese) there really are no other strict rules about writing haiku, because if there were, they are constantly being broken, but I could be wrong. I shall refer, for examples, to haiku on this website: http://thegreenleaf.co.uk/hp/basho/00Bashohaiku.htm

Before I go any farther, let me say that the following quotation has been attributed to Bashō: “A haiku presents a pair of contrasting images, one suggestive of time and place, the other a vivid but fleeting observation.” So we should add to our definition that haiku are supposed to give us images in words relating something the poet sensed. Bashō’s “old pond” poem is the prototypical haiku.

the old pond

a frog jumps in

the sound of water

It has the 5-7-5 pattern (3-4-4 in English) and there is a clear distinction between the first line and the last two. Bashō did not write this as a run-on sentence, but gave us the image of the old pond, paused, then told us what happened there. One could write any number of haiku based on this pattern, and many have been written. For example, one might write,

old town –

a pigeon lands in

the sound of traffic

This is faithful to the original layout of Bashō’s poem. I don’t claim my example is as good as Bashō’s, but it is a haiku, and if you want to write haiku, this is one way to do it. Later we will discuss other ways of structuring haiku.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 11, 2012

Happy Daylight Savings Time. So, the old pond poem gives us an image of a frog jumping into a pond. Is this the only way to write a haiku? By all means, no. Many times, instead of putting the image of time and place first, as in “old pond,” the poet puts it last. That doesn’t work for this particular poem. It wouldn’t make much sense to say

a frog jumps in

the sound of water

old pond

one possibility might be to say

the sound of water

a frog jumps into

the old pond

But that’s getting it backwards, which brings up an interesting issue: many times when writing a haiku, it becomes a matter of deciding which order to put the images. Also, there is a great temptation to blurt out the punchline first, because that is what you’re excited about, and you want to share it immediately with the reader. But the writer of the haiku should endeavor to recreate that haiku moment for his reader, and surprise is part of that, so often it is better to maintain the tension, and place the most important image last.

A better example than the one above might be (and I am going to try and use examples from my own poetry here):

flock of geese

walking across the street –

rush hour traffic

Now I could have put “rush hour traffic” first and it would have had the same structure as the “old pond” poem. As it is now, however, the structure is inverted. This happens a lot with haiku. If you look at the poem that begins “slender, so slender” (on this website: http://thegreenleaf.co.uk/hp/basho/00Bashohaiku.htm ) you will see that Bashō uses this inverted structure as well. (You know how to “find” things on a page, right? On the PC it is control+f then type in what you’re seeking to find. I’m not sure what it is for a Mac)

Taken as a whole, my haiku here creates a striking image, one of geese walking across the street during rush hour traffic. It is a dynamic poem that captures one instant in time. It remains objective, much like a camera lens. That lack of subjectivity is a characteristic of some classical haiku. On the other hand, some classical haiku are subjective, like those of Issa, for example.

On a serious note, this poem is particularly poignant for me. One of my neighborhood geese was run over by a car and killed yesterday as it was trying to cross the street, so that is one more dimension the poem has for me.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 12, 2012

First, let me say something about “the haiku moment.” Basically it is a moment of insight, inspiration, a moment when you say “AHA!” Sort of like Archimedes when he was sitting in the tub and suddenly realized the solution to his problem. Jane Reichhold writes extensively about the haiku moment here, the first part of which I suggest you scan: http://www.ahapoetry.com/haiartjr.htm (her website address is even called ahapoetry!)

Now, moving on: In yesterday’s post I mentioned objectivity and subjectivity in haiku. Here is what I meant: something like the “old pond” poem is objective. The poet sees a frog jump into a pond, he hears the splash, and he writes down what he saw and heard. He does not inject any personal (subjective) material into the poem. Nor does he interpret what just happened and tell us what it means. For one thing, he only has 17 syllables to convey his images. For another thing, most classical haiku, it seems to me, is written from a detached, objective point of view. One last thing: if a poem has more than just one meaning, it is up to the reader, not the writer, to provide that. As a writer I have always heard the dictum “Show, don’t tell.” That’s what I mean here: with haiku we try to show the reader what happened, not tell him. We use images to show him.

I prefer to write objective haiku. When I experience a haiku moment, I feel that it is possible to convey that experience to others. After all, we’re all human, we all have similar responses to things, and if I say “old pond / a frog jumps in / the sound of water,” I have communicated something that most people will respond to in a similar manner. At least all writers hope they are able to communicate effectively.

The idea for most haiku is to make a poem so that the reader will say “AHA” just as you did when you had the experience. We often do that by making our poems out of objective, commonplace materials. Haiku Master Buson said, “Use the commonplace to escape the commonplace.” If we present our ordinary materials truly enough, they will transcend their ordinariness.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 13, 2012

Yesterday we discussed objectivity in regards to haiku. Let me give a few examples of objectivity. (These and all future examples of Japanese Master haiku are taken from a public domain book, Japanese Haiku, by Peter Beilenson, 1955 ~ http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/jh/jh00.htm )

in the sea-surf edge

mingling with bright small shells ..

bush-clover petals ~Bashō

This poem has basically the same structure as the old pond poem. “in the sea-surf edge” is essentially the same as “the old pond,” an image that sets the place for us. Bashō is painting us a picture here. Another way of putting it is that he is telling us a story. And as he is doing that, he maintains tension. He could have said, “there are bush-clover petals mingling with bright small shells in the sea-surf edge” If you were telling somebody about them, chances are that is the way you would tell it. Haiku is mostly about surprise, though – after all, your haiku experience was basically a surprise to you, and you are trying to create that same surprise for your reader – and so he builds up the picture until revealing the thing that surprised him: the bush-clover petals. Note also that this is one haiku that you do not want to invert. It just doesn’t work that way.

Another example:

black cloudbank broken

scatters in the night … now see

moon-lighted mountains! ~Bashō

The language here is about as objective as you can get. We’re looking at the sky, the clouds break apart, and suddenly we see moon-lighted mountains. Once again painting a picture, revealing a scene, maintaining tension until the most surprising part is at last revealed. We could have said, “Now I see moon-lighted mountains as the cloudbank breaks and scatters in the night,” and it might be our natural tendency to show it that way. I find myself trying to show it that way all the time. But that is not the way most writers of haiku would do it. They would save the mountains for last. As we discussed before, the way we order our sentences is very important. Also, going back to Bashō’s dictum of the two images, he sets the scene with the image of the cloudbank, then the moon-lighted mountains are his fleeting observation

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 14, 2012

If I may digress a moment, yesterday on Twitter someone retweeted one of Bashō’s poems, and it went something like this (I made this haiku up for illustration purposes):

a squirrel

standing on the dry birdbath

in my front yard

So I asked those in my Twitter stream, which is better, the above haiku, or this one:

in my front yard

standing on the dry birdbath

a squirrel

@pamrosypp said she liked the first version because it was easier to read, although the second saves some mystery til last. @kokeesashdeva from India noted that the first version sounds better, but the second version is more artistic. When I pointed out that haiku is largely about epiphany, Pam said she understood, that it’s somewhat like hide and seek. @invincwil said he too liked the backwards linear development of version two, as that leads to the ah-ha! haiku moment.

One quick point: version one would have been some translator’s version of a Bashō haiku, and it just shows you that even translators can get it wrong.

I told @vonguyenphong22 that often haiku should be like a flower that opens, opens, opens, ah-ha! Version one is a nice image, but version two is a haiku. It may not be as great as a Bashō haiku, but it is similar. Also, when we tell someone what we saw, we are naturally inclined to structure it like version one. But for artistic purposes, we should structure it like version two, if we want to make a haiku. Anyway, I just thought this was a good, instructive example. This doesn’t mean that all haiku should look like this, but in this case version two is a better haiku.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 15, 2012

Tuesday I had a discussion with several people on Twitter. Someone asked me if I favored the structure of 5 7 5 syllables in English language haiku. Of course this is the structure that most if not all classical Japanese haiku employed. Since I write English haiku and not Japanese haiku, I favor a more flexible structure. That’s not the only reason. The way I do haiku now is challenging enough for me, and I enjoy it, and I see no reason to try and adhere to such a strict format. Anyway, my approach is this: my English haiku should have no more than 17 syllables in all, and no line should have more than 7 syllables.

During the discussion Tuesday, Hemant noted that some of the haiku we see have syllable counts that exceed those limits. I explained that haiku translated into English often have unusual syllable counts because the two languages are so different. Then he noted that he felt 5 7 5 was the benchmark for proper haiku and wondered what was the correct structure. My response was that in English there is no correct structure because different haiku poets use different formats. I’ve seen haiku in one line, two lines, etc.

Tina had been following our conversation and commented that yes, 5 7 5 structure is not needed in English haiku. She gave the following website in order to bolster that claim https://sites.google.com/site/graceguts/essays/urban-myth-of-5-7-5 This article notes that Japanese and English are very different languages, and that the Japanese are not counting syllables at all, but sound units. Also, the author of this article admits that she wrote very bad haiku until she stopped focusing so much on form and started focusing more on content – i.e., what she said instead of how many syllables she used.

Linda joined the conversation and said that she likes the 5 7 5 challenge. Hemant likes the 5 7 5 challenge also. Tina posted this address http://www.hsa-haiku.org/archives/HSA_Definitions_2004.html#Haiku which contains the official definition of a haiku as presented by the Haiku Society of America. So this seems to answer Hemant’s question about what is the correct form of an English haiku, at least according to the Haiku Society of America. I suggest you read this definition.

In the final analysis, people will do what they want to do, and that is good. Hemant and Linda may stick to 5 7 5, whereas Tina and I may concentrate more on content. As Tina said, we should enjoy writing poetry. If we don’t enjoy it, why bother? I agree.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 16, 2012

We spoke recently about objectivity in haiku. Now I would like to talk about subjectivity. Of course, a haiku represents a subjective experience which we seek to put down on paper objectively. The way we do that is by our choice of which experience to try and capture, our choice of details, our choice of words, even by the order of our sentences.

There’s no way to escape some subjectivity. Poetry is a subjective art. If we try to do it objectively, still our subjectivity creeps in. I will say, however, that the initial experience we have goes a long way in determining what sort of haiku we end up with. So if you see a frog jumping into an old pond, it’s pretty difficult, though not impossible, to talk about something else.

It seems to me that Issa is a haiku poet who displays a great deal of subjectivity in his poems. For example (http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/jh/jh03.htm):

What a peony . . .

demanding to be measured

by my little fan!

In this poem, Issa is obviously projecting his own thoughts and imagination onto the peony, because the peony is just a flower and has no thoughts or demands of its own. Issa frequently tells us what he’s thinking instead of telling us what he sensed:

Hi, kids mimicking cormorants

you are more like real cormorants

than they!

Issa sees a scene, and he responds to it with something like a joke. Another person seeing the same scene might well have had an entirely different response. Also, this is a bit of hyperbole, because no kid acts like a cormorant better than a real cormorant.

And of course you may ask, is it ok to write haiku like Issa instead of like Bashō or Buson. The answer, of course, is yes. There are many different ways to express yourself poetically, and Issa’s way, subjective as it might sometimes be, is one valid way to do it. Furthermore, even Bashō and Buson have their flights of subjectivity at times. (By the way, I suggest you read some more of Issa’s haiku. You can read a lot of Issa haiku here: http://thegreenleaf.co.uk/hp/issa/00haiku.htm )

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 17, 2012

Of course, Issa is not the only one who writes haiku that could be considered subjective. Here is an example from Raizan (http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/jh/jh02.htm):

women planting rice

every bit about them ugly

except their ancient song

I don’t know why Raizan chose to write about the perceived ugliness of the women. To me that is merely his opinion. I doubt that everyone would think the women ugly. For example, all children think their mother is pretty, regardless of what the world thinks about them. I know there have been times in history when people have done and said things without regard to the feelings of others, and I suppose this is one of those instances. But I really think that sentence says more about the author than it does about the subject. It would have been much better, I think, if he had said something like

women planting rice

so lovely

their ancient song

I know that the word ‘lovely’ is a subjective value judgment, but it’s better than ugly, isn’t it? Also, changing it the way I have makes for a simpler poem, and it is my opinion that simpler is better when it comes to writing haiku. According to my experience, I have found most classic haiku to be very simple.

Here is a poem from Bashō:

twilight whippoorwill

whistle on, sweet deepener

of dark loneliness

If there is any emotion connected with birdsong, that is really from the listener’s point of view. In this poem Bashō is feeling his loneliness, and the whippoorwill’s song is intensifying that feeling for him, so this whole poem is very subjective. There’s nothing wrong with that. Bashō is probably the greatest of haiku masters, but in his greatness he is multidimensional: some of his poems are objective, and some are subjective. In the final analysis, he is just a man expressing himself poetically.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 18, 2012

Yesterday I wrote and posted this poem:

women planting rice

so lovely

their ancient song

Before moving on, let’s touch on one other thing: in the poem, what am I describing as lovely? Are the women lovely? Is the song lovely? The answer to both questions is yes. Line two, “so lovely,” can be read along with either line one or line three. With many poems there is only one way to interpret it – only one meaning. That’s all right, but I like to add meaning to my haiku sometimes, and one way to do that is by making them ambiguous.

For example, in this haiku of mine, also one of my favorites:

gray winter day

so mournful

distant train whistle

Of course, either the day or the whistle could be thought of as mournful, and line two could be read along with line one or line three.

I have been writing for almost fifty years, and in all those years I have read a lot about writing, art, etc, and many things I have read suggest that ambiguity often makes for a better work of art. The artist wants their work to be capable of multiple interpretations. (Just think of all the different interpretations of Hamlet, for example, and all the books and dissertations that have been written as a result.) Sometimes this is accomplished on purpose, and sometimes it happens accidentally. In the above poem, I did not set out to make it ambiguous. I set out to change a word I found offensive. But in the process it ended up ambiguous. And the reader, I believe, can find pleasure in a work’s ambiguity – if he or she notices it, that is. And hopefully this discussion will help you see more meaning in the poems that you read and write.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 19, 2012

Recently I mentioned simplicity in haiku. Much haiku is very simple. After all, the poet is dealing with only seventeen syllables. But I get the impression that the beginning haiku poet tends to unnecessarily complicate his or her poems. And perhaps that tendency is not limited to beginners. When you are trying to write a poem, it’s natural if you want to convey as much information as possible, to explain or show enough so that the reader will understand you. When writing haiku, though, one must be selective with his detail. Not only that, sometimes one must leave out details for the sake of brevity, or even just to remain within the 17 syllable limit. AND, however distasteful it might seem, sometimes it becomes necessary to change details to fit the poem, all the while trying to maintain the same impact of the original thought. Sometimes I’ve had to make something blue instead of purple because the extra syllable put me over the limit.

In my reading and study of haiku, Buson has always stood out as a prime example of someone who wrote simple poems. Look at this poem (I wrote it, trying to mimic Buson’s style):

old dog

asleep

on his dinner dish

If you look at this, you have three elements here: dog, sleep, dish. Other poets might have combined the first two lines and added a different line one. They would not have been wrong to do that, but Buson’s simplicity has its appeal. His haiku remind one of how an artist might use a series of brush strokes to make an impressionistic drawing. Buson does the same sort of thing with words to convey this type of image. Here is another example:

thunder rumbles

and the azaleas

tremble

He cuts the image down to its bare minimum. By doing that, I think he intensifies its impact. One would do well to read and study the haiku of Buson. Here is a website with a number of his poems. http://thegreenleaf.co.uk/hp/buson/00haiku.htm Also, if you have a copy of The Essential Haiku by Robert Hass, I like the poems in that book.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 20, 2012

Yesterday we discussed Buson and simplicity. Buson was one of the three great haiku masters of antiquity, as well as a painter, which may explain the visual nature of his haiku. You can read more about him here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yosa_Buson Today I would like to take a closer look at some of his poems in the public domain book Japanese Haiku by Peter Beilenson (http://www.sacred-texts.com/shi/jh/jh00.htm) It seems to me that translators often unnecessarily complicate things because some of the haiku in this book could benefit from editing. For example

A. standing still at dusk

listen . . . in far distances

the song of froglings! ~Buson

I think this translation could be improved thus:

B. standing still at dusk

listen . . . the distant song

of frogs

This is better. There is such awkward language in version A.: ‘in far distances’; ‘song of froglings.’ Even my words processor doesn’t like ‘froglings.’ Also, however, there is another possibility here:

C. standing still at dusk /

listen . . . the song /

of distant frogs

I like ‘the distant song / of frogs’ better, version B, but it does illustrate the point that there is often more than one valid way of expressing the same haiku.

But wait!! Here is a version that I might like even better:

D. standing still at dusk

listen . . . a song

of distant frogs

All I’ve done between version C and version D is change one word – from the to a – but to me the change is significant. When I say ‘a song’ I am building up an expectation in the reader. They aren’t sure what to anticipate, except that it should be a song, and it probably should be fairly conventional. Then when I finish by revealing the frogs, there is a sense of surprise, which I think is often very satisfying. Most great art is built on surprise, from poetry to string quartets. Yes, haiku are simple, but that simplicity can be deceptive, as this discussion suggests. (For the record, having thought about it more, I like all the revised ones, and often it becomes a matter of just choosing one and going with it.)

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 21, 2012

Many haiku are written (or translated, I never know which, since I don’t speak Japanese) as run-on sentences. Take this from Bashō for example:

A. lady butterfly

perfumes her wings

by floating over the orchid

This is just a run-on sentence. It is not structured according to Bashō’s dictum of the two contrasting images. One can imagine Anderson Cooper saying something like, “and now lady butterfly perfumes her wings by floating over the orchid.” OK, well maybe not Anderson Cooper, but you get the point, this is a nice image, but it does not seem like a haiku. Is there any way to rehabilitate it? We could try something like these:

B. over the orchid

lady butterfly floats

and perfumes her wings

C. floating over the orchid

lady butterfly

perfumes her wings

D. floating over the orchid

and perfuming her wings

lady butterfly

E. lady butterfly

floats over the orchid

and perfumes her wings

I don’t know, in many ways the original version A is the best, and I guess I would be inclined to leave it at that. It has some of the simplicity that we spoke of in relation to Buson’s work, which is good. It leaves us with a nice image of a butterfly floating over the orchid, and it is usually a good idea to leave your reader with a visual image. So I guess the conclusion here is that sometimes haiku are written as run-on sentences, and that’s ok. If Bashō did it, then it must be OK, right? I think so.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 22, 2012

As we discussed earlier, there is a difference between an image and a haiku, although an image can be a haiku. Take the poem from March 19

old dog

asleep

on his dinner dish

This is just an image, an old dog asleep on his dinner dish. Many master haiku poets, however, write poems just like this, and they are considered to be haiku. Basho wrote a poem like this:

a white butterfly

getting lost on a bush

of white azaleas

Nice image, but just that, an image. Then Issa:

cruel autumn winds

cutting to the very bones

of my poor scarecrow

Say what you want to about this, but it is merely an image. Perhaps I shouldn’t say ‘merely,’ because it is a great image. Try this, also after Issa

blackbirds

strutting in my yard

like they own the place

This is really just an image, and I don’t consider it to be a great haiku. It is possible, however, to rehabilitate most of these images. The ‘poor scarecrow’ image really is great. I have thought about it and so far there is nothing I would change. I’ll let you know if I come up with anything. The others, though, could all benefit from being inverted. Then I think you would end up with haiku like these, which are not really bad:

asleep

on his dinner dish

the old dog

getting lost

on a white azalea bush

the white butterfly

strutting in my yard

like they own the place

blackbirds

So you see, it is possible to repair many poems. It helps, though, if you’re familiar with haiku structure and theory.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 23, 2012

I began this haiku discussion on March 10 by hypothesizing that there were no strict rules about writing haiku other than the 17 syllable rule, the three line rule, the 5 7 5 pattern rule, and an additional rule that a haiku should consist of images. I think we have seen that, for the most part, my hypothesis is correct. Not only that, but many English language haiku and translations at times break all the above rules (that’s an important point) except maybe for the rule about consisting of images. We have discussed run-on sentences and solitary images, and concluded that even though many of those are considered to be haiku, they do not adhere to standard haiku rules. The conclusion I draw from all this is that the writer is free to write haiku almost any way he or she sees fit. If Bashō wrote a run-on sentence haiku, then I can write one like that too. If Buson wrote a haiku that was merely an image, then so can I. (In fact, Bashō said to learn the rules and then forget them.) There is at least one exception, though: I do not think something like this would ever constitute a haiku:

I went downtown

bought a newspaper

and then I came home

Why is this not a haiku? For one thing, it is a simple declarative sentence, and most simple declarative sentences are not haiku. For another thing, there is no surprise involved here. Most, if not all haiku occur when someone is wandering through the world and suddenly encounters something unexpected, surprising. There is nothing unexpected or surprising in that declarative sentence, no “haiku moment,” nothing to make one say “ah-ha!” It is merely someone relating what he did on one occasion. Anyway, I’ll talk more about this tomorrow.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 24, 2012

One reason I mentioned all I did before was to show you the different ways that poets have written haiku. Bashō, Buson, and Issa have all written images and run-on sentences like those we have seen and have called them haiku. Another reason I mentioned it, however, was to point out what to avoid. It’s nice to write nice images. I like to do that myself. It’s nice to write run-on sentences. But many publishers today will not publish images or run-on sentences like those. If you try to get them published, there is a good chance, in my opinion, they will be rejected. I’ve had many rejected myself. Publishers want haiku structured like haiku, sounding like haiku, etc. Sometimes I wonder if Bashō, Buson, and Issa could get much of their haiku published today.

I don’t know how many of you have read Writing and Enjoying Haiku by Jane Reichhold. Ms. Reichhold is an acknowledged haiku expert, and her book is a must-read for every haiku poet. But much of her book is available to be read in various articles online starting here: http://www.ahapoetry.com/haiku.htm

Personally, I continue going back to Bashō’s dictum: “A haiku presents a pair of contrasting images, one suggestive of time and place, the other a vivid but fleeting observation.” But let’s see what Ms. Reichhold has to say before moving on.

The above website serves as a sort of hub of information, with links to articles further down on the page, and to other pages.

This link farther down the page http://www.ahapoetry.com/haiku.htm#frag talks about the Fragment and Phrase Theory. (NOTE: this article is all run-together. If you scroll through it til you get to the boldface heading Jane Reichhold, you find the same article formatted well.) Let me begin by saying that since I know that haiku rules are constantly being broken, I tend to not like any theory that locks me into a certain form. I also tend to be guided by an idea instead of a form, as we discussed on March 15. If I can fit an idea into a certain form, as with Bashō’s dictum mentioned above, no one is happier than I. However sometimes I allow the idea to take or find its own form. That does not mean, though, that I dismiss the form completely. But I do try to use what works for me, as everyone should, although it never hurts to try new things.

Having said all that, something like the Fragment and Phrase Theory or Bashō’s dictum can help a poet find a form for his or her poem, and in a case like that, I am all for it. So, read the article on the Fragment and Phrase Theory and we’ll continue our discussion tomorrow. Thanks.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 25, 2012

I hope everyone read the article about the Fragment and Phrase Theory. Jane Reichhold goes through a number of examples in this article as I have been doing and explains the rationales behind some of her choices. It is always good when someone like her explains what is going on in her mind.

The Fragment and Phrase Theory in reality is not that different from Bashō’s dictum. Both are divided into two parts. There is a pause between the parts. Notice Reichhold suggests that if you accept the Fragment and Phrase Theory, that means you reject the run-on sentence.

Coming out of what I consider to be the Bashō School of haiku poetry, I admit that I’m not a big fan of the Fragment and Phrase Theory.

One thing that she did not seem to explain, as far as I could see, was where she gets the Fragment, and where she gets the Phrase. With Bashō’s dictum, it is clear: one image of time and place, another fleeting but vivid observation. I don’t know, maybe I’m focusing too much on terminology. But if you read the first few paragraphs of Reichhold’s discussion, she admits there are many rules to choose from; the haiku community is so diverse that it seems there are no “real rules”; and the Fragment and Phrase approach just seems to be popular and widely used at the present time.

Anyway, I know from personal experience, and much research, that there are some perfectly good haiku that do not fit into Bashō’s scheme, or Reichhold’s scheme. Many of Issa’s poems are like that, perhaps even the “poor scarecrow” poem we looked at March 22. Often Issa makes up his own form, and his wonderful, witty personality shines through. Anyway, I think it would be crime to let the rules inhibit your having or writing down a creative idea just because it didn’t fit into one of these forms.

Next time we’ll discuss Another Definition of Haiku http://www.ahapoetry.com/haidefjr.htm

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 26, 2012

In Jane Reichhold’s “Another Attempt to Define Haiku,” (http://www.ahapoetry.com/haidefjr.htm) she gives a brief history of the haiku form, then she gives a couple of examples from Bashō, the “old pond” poem where I guess what she would call the Fragment comes in line one, and another poem where it comes in line three (i.e., inverted, as we have discussed.)

She seems to agree that 5-7-5 is not necessary, particularly for the sake of brevity and editing out superfluous words. She advises to avoid adjectives and adverbs, but not to eliminate them entirely. However she does acknowledge that often you need a modifier for clarity. I agree with all this. In looking over some of my haiku just now, many of them are devoid of adjectives and adverbs, as they should be, so that’s good.

There is a lot of good advice here. I particularly like Reichhold’s emphasis on revising haiku, editing them, improving them, not leaving them alone until you’re really satisfied with them. (By the way, on pages 73-75 in her book, Ms Reichhold gives “A checklist for revising haiku.” This list contains 19 suggestions for improving your haiku. This checklist is also available on this web page: http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless12.html Isn’t the internet a wonderful place for finding information? I think so!) I do have one thing to say here: suggestion #11 says to be specific. Don’t just say tree, but rather say oak, or pine, etc. That’s all well and good, but I would not throw away a perfectly good haiku just because you don’t know you’re talking about a catalpa tree, or a dogwood, whatever. There are many instances where master haiku poets readily admit they don’t know the name of something like a tree, a flower, even a mountain, and that kind of honesty and humility is inspiring.

Tomorrow I would like to look at these two web pages

http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless9.html

http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless10.html

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 27, 2012

There is one other point to make regarding her “Another Attempt to Define Haiku.” Ms Reichhold also suggests that we imitate haiku that we like. I think that is a very good idea. We can learn a lot by imitating the poems of master haiku poets, although as I mentioned before we need to remain current. Haiku seems to have evolved over the years, and in English, and it never hurts to see what’s being done now. I hope to delve more deeply into that in a couple of days ![]() )

)

Now, this page, “Lesson nine: finding your own rules for haiku” (http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless9.html) is actually taken from pgs 75-79 of Reichhold’s book. This article contains 65 haiku rules for you to choose from. Reichhold admits that you can’t follow all the rules or suggestions because many conflict. So each person chooses his or her own rules. For me personally I like rules 21, 22, and 24. I notice that rule 17 suggests eliminating all ‘-ing’ words, so maybe that’s where I once got the mistaken impression she was against them altogether. Anyway, I also like rule 65. Read through these rules and see what you like. Many of them are like prompts to stimulate you and for you to try, like trying to write sonnets or sestinas with their rigid forms.

This page, “Lesson ten: Haiku Techniques,” is really great: http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless10.html It is also taken from Reichhold’s book, and in the book it is like 24 ways you can classify haiku, or techniques for writing them. For example, you can write comparison haiku, or contrast haiku, etc. I’m not sure what good the list does except as an academic or intellectual exercise, but it can serve to give you ideas for writing your own haiku. It would probably take the student much study to internalize all these points, but one thing he or she could do is take them one by one and imitate them. That way you get a better understanding of them and have them stimulate your own imagination.

Tomorrow let’s look at this article: http://simplyhaiku.com/SHv7n1/features/Kai.html

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 28, 2012

I would like to say a few words about this article sent to me by Scott Reid http://simplyhaiku.com/SHv7n1/features/Kai.html . At the very beginning Hasegawa Kai talks about humans in nature and says that in Japan “humans are thought of as being a part of nature.”

Jane Reichhold in her book suggests that for a long time human activity was not considered, by some, to be proper subject matter for haiku (pgs. 38-39) although if you read the masters Bashō, Buson, and Issa you might come away with an entirely different impression, because Bashō sometimes talks, for example, about monks sipping morning tea http://www.eliteskills.com/c/20068 ; Buson mentions his dead wife’s comb http://khushdalal.wordpress.com/2011/07/14/the-peircing-chill-i-feel-taniguchi-buson/ ; and this poem by Issa certainly deals with human concerns http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/writing-shit-about-new-snow/

In my haibun ebook Birds Don’t Write Poetry I wrote “if you see something that excites your imagination, you can write about it, not just from the point of view or perspective of a detached observer, but also as a human being who is involved in the scene, and who experiences a human response. After all, we as humans are not separate from the environment, we are part of it, and we can write poetry as an active participant in the totality of nature. Birds can’t write poems but we can, and writing poems is part of our role in nature.

birds

don’t write poetry

they live it

“Having said all that, I think it may be important for the poet to write down what caused him to have his response – the images, not simply the response itself. So instead of telling you what I think about something, I try for the most part to show you what I actually saw.”

Though it might seem there are contradictions or paradoxes between what Hasegawa Kai says and what Reichhold says, really there aren’t. (read this article http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless7.html) They both agree that human activity belongs in haiku, and those who think it doesn’t are mistaken, as a careful reading of the Reichhold article shows.

Regarding the Hasegawa Kai article, I agree with Scott Reid that it is interesting and worth reading in its entirety, although some people may find it a bit theoretical for their taste.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 29, 2012

What is the difference between a haiku and a senryu? Many people like to apply the simple formula that if the poem is about nature it’s a haiku, whereas if it’s about humans it’s a senryu. But we just got through saying that humans are a part of nature, so what is a senryu, and how does it differ from a haiku?

Those who have read yesterday’s article (http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless7.html ) know the answer to that (also 39-41 in Reichhold’s book). Basically a senryu is a haiku which, in Japanese, does not have a season word. So I guess that means that everything else is a haiku, if it otherwise fits the criteria of a haiku. What about English? I call all the poems I write ‘haiku’ whether they are about nature or humans. Jane Reichhold seems to agree because she says, regarding poems whose subject is humans, “and still, the proper name for the work is haiku.”

Also regarding this article, under the heading “Using Sensual Images” you can see that Reichhold agrees with what I said yesterday about writing down the image not what you think.

This is a good article. Not only does it discuss sensual images, but at the very end it mentions “Personification,” which is, I guess, attributing human qualities to non-human things, something she says we should not do. In my haibun ebook Birds Don’t Write Poetry I actually discussed that theory:

on my backyard table

dancing

raindrops and sunshine

Sometimes it rains while the sun is shining, and that’s what happened here. I looked out my back door and saw raindrops bouncing up and down on the glass table, and the sun was shining on all that. I like the word dance. Properly speaking, maybe it should only be applied in relation to humans – dancing is a human activity – but I like to apply it to things in the natural world as well. (I think that’s called the pathetic fallacy. Frankly I don’t care.) And if they can talk about the music of the spheres, I can talk about dancing raindrops. Besides, it’s a matter of perception, isn’t it? No perception, no haiku. So I perceived raindrops dancing. Anyway, this is one of my favorite poems. I love this image.

Anyway, Reichhold is not wrong in her recommendation. But if it makes me happy to talk of dancing raindrops, then I’m going to talk of dancing raindrops, thank you very much.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 30, 2012

For awhile there I was referencing this website: http://www.ahapoetry.com/haiku.htm But I discovered that this website has much the same information, and it looks better, and may be better organized: http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/bbtoc%20intro.html Anyway, it doesn’t hurt to have both.

Earlier we talked about the many techniques for writing haiku http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless10.html

In this article, lesson 11: http://www.ahapoetry.com/Bare%20Bones/BBless11.html Reichhold talks about 33 of those techniques in relation to Bashō’s haiku. Reichhold translated all of Bashō’s haiku and published a book Bashō: The Complete Haiku. The 33 techniques, with their discussions, are taken from that book. (You know, this is a really good deal. On these websites she is giving you for free things that she has published in her books and charged you money for. And it is really great to be able to sit, as it were, at the side of a master like her and listen to her explain things the way she does, so take advantage of that, it is really a great opportunity to learn.)

One thing I must mention, however, for full disclosure, whatever: if you look at the haiku accompanying technique #16 in lesson 11, for example, what you find is an image or sentence fragment or run-on sentence, however you want to characterize it. The same is true of 7, 8, 19, and 23. These are all things that Reichhold has advised against, so as you see, and as I’ve said, the ‘rules’ are constantly being broken. And yes, learn the rules, then forget them, I suppose?

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com

March 31, 2012

I think it is important to study classical haiku, but it is also important to know what is being done today. To give you some idea of what haiku publishers are looking for now, these poems won the HaikuNow! haiku contests: http://www.thehaikufoundation.org/haikunow-archive/ Let’s take a look at some of them.

Tom Painting won first prize here. (Notice the category is Traditional Haiku, that is, these poems all conform strictly to the 5-7-5 syllable pattern, which is no easy thing to do, I can tell you.) Painting’s haiku is probably traditional in every sense of the word, in that it pretty much follows Bashō’s dictum of the two contrasting images that we have been discussing – time and place, followed by a vivid but fleeting observation – although the first image is more time than place, and the second image is somewhat vivid (certainly full of color) but doesn’t seem too fleeting. However, it could have seemed fleeting to the observer.

Melissa Spurr’s haiku is nice, although it seems like a run-on sentence. Also, line 3 is very subjective. I’m not against that, I’m just saying that if haiku are supposed to be objective, this one seems subjective.

Christopher Patchel’s haiku: once again, nicely structured. The first image seems more like time than place and the second image seems vivid enough but not very fleeting.

Frankly I would have given the prize to Marion Alice Poirier. I like her poem. It too is rather subjective, but it’s perfectly structured, in my opinion, and it leaves us with an image to which many of us can relate. (In poetry generally it is usually good to leave the reader with a vivid image.)

Let me say, however, that I take my hat off to all these poets and their poems. 5-7-5 is not an easy feat to accomplish, and all of these poets have accomplished it with a high degree of excellence!!

Also on this page are the winners in the Contemporary Haiku category (here’s the criteria http://www.thehaikufoundation.org/haikunow-contemporary-haiku) and the Innovative Haiku category. Structurally the contemporary haiku don’t seem all that different except for the more flexible syllable count. And regarding content, we do find some subjectivity and personification.

Here is another website that publishes contemporary haiku, with many examples for you to study: http://www.dailyhaiku.org/haiku/

This is my last day as guest blogger here. I have enjoyed discussing haiku, and I even learned a thing or two during this time. I hope you have enjoyed the discussions as well. Thank you for the opportunity to be your guest blogger for the month of March.

Please visit my haiga page: http://edbremson.blogspot.com Thank you!!

You can follow me on Twitter @EdBremson

email: eddie80 (at) yahoo (dot) com